After a decade of austerity and the trauma of a two-year long pandemic, the UK’s public sector workers deserved some respite come 2022. Instead, they are now enduring the largest real wage cuts in recent history.

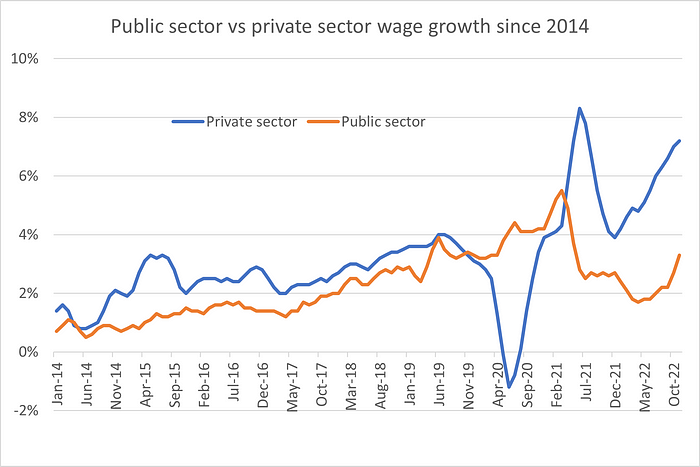

Average settlements on offer to public sector workers are currently around 3% with inflation at 10%. This 7% cut in real wages amounts to almost a month’s salary not being paid. Furthermore, the private sector is enjoying wage deals more than twice as high at around 7% as shown in Figure 1.

Under such conditions, the withdrawing of labour is an entirely rational response. It is even more understandable when you consider the wider macroeconomic policy regime that appears rigged against the public sector.

The argument being repeatedly made by both the government and the independent Bank of England is that paying public sector workers close to or above the current rate of inflation would be self-defeating because it would lead to higher prices. This is due to the so called ‘wage-price spiral’ where higher prices lead to calls for higher wages which then feed through to higher prices and so on.

There are four reasons this argument is flawed.

Firstly, in capitalist market economies the public sector does not set prices, firms do. So the wage-price spiral can only apply to the private sector in as far as it is a direct relationship between wages and consumer prices.

The only way the government could finance additional wages for the public sector would be raise taxes or borrow more. Taxing directly removes money from the economy so it is difficult to see how this could be inflationary.

Borrowing involves investors spending money buying government debt instead of other assets. Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has stated this would affect “overall demand in the economy” and force the Bank to raise interest rates, further adding to the cost-of-living crisis facing low paid workers.

There is evidence that bond financed fiscal deficits are associated with higher inflation. But this relationship is almost exclusively found in developing countries with weaker institutions and tax raising powers, not in high income economies like Britain.

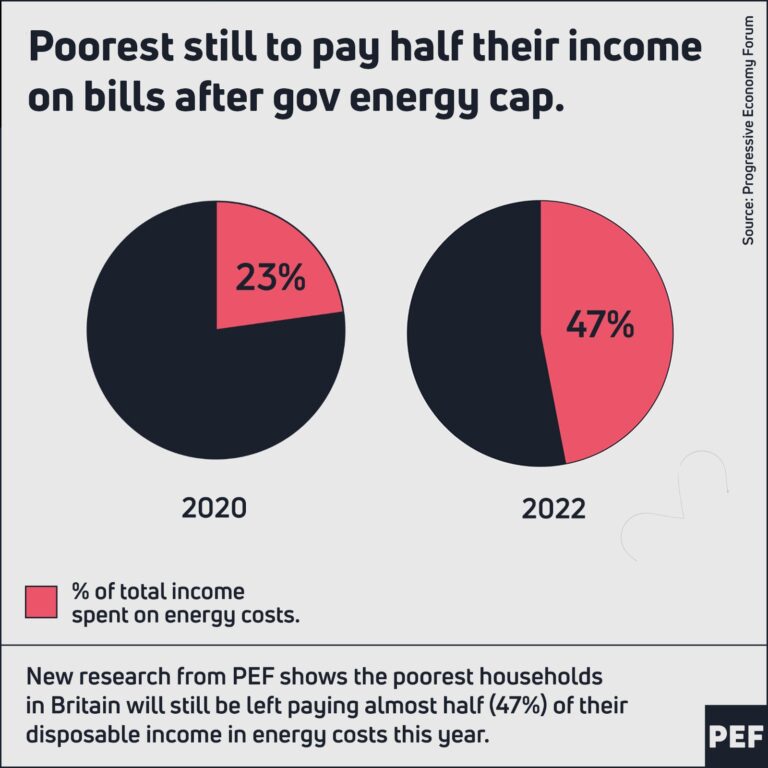

Second, current inflation in the UK is mainly driven by supply-side factors, in particular rising energy prices caused by the Ukraine war feeding through to other sectors. There is evidence that rising energy costs have led firms to raise their prices and evidence that other firms have exploited the situation of rising prices to use their market power to raise prices above inflation, generating excess profits. If anything, there is more evidence of a ‘profit-price spiral’. None of this has anything to do with what public sector workers are paid.

Thirdly, public sector workers make up only around 17% of the workforce. Thus inflation-linked wages to help public sector workers catch up with years of real wage cuts would have much less impact on total demand in the economy than they would in the private sector.

Finally, the public sector is suffering from a serious shortage of labour caused by the COVID pandemic and difficulty recruiting workers from the EU post-Brexit. In particular the healthcare sector is in crisis, making up 13% of all jobs advertised in the UK last month.

Keeping wages well below those available in the private sector — which they have been over most of the past eight years (Figure 1) — will make the situation worse as employees are more tempted to leave. In turn, this will require even larger pay increases down the line to bring workers back.

Given flatlining growth, fears about excess demand and entrenched inflation have to be tempered with the risk of rising unemployment and even more individuals leaving the workforce, worsening an already extremely weak macroeconomic environment.

Striking public sector workers have the support of the majority of the public. They seem to recognise, better than the politicians and policy makers in charge of our economy, that a strong public sector is the building block for sustainable economic growth. Let us hope that those taking industrial action succeed in pushing through higher wages for all our sakes.

This blog was first published on 14th February 2023 on the official blog of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose | Rethinking how public value is created, nurtured and evaluated | Director @MazzucatoM | https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/