PEF Council members recently discussed, via email, the government’s plans for social care and its financing. We were unanimous in agreeing on the bad design of the scheme, on the absence of real funding and reform for social care. And we also agreed on the need for a significant shift in the balance of taxation towards wealth. The points of contention are around how the latter should take place and a macroeconomics that might help explain why.

Stewart Lansley

The case for financing social care through wealth is overwhelming. There are two broad options: first, the 2010 Burnham Plan, which means all those needing care would keep their home and a charge made at death. Alternatively, an annual property charge of say 1% pa up to say a maximum of 5%. Both of these could be paid into a social care fund, as argued in Remodelling Capitalism.

The last two decades have seen a great surge in asset values and unearned wealth (what John Stuart Mill called “getting rich in your sleep”), notably in property. The total value of personal wealth in the UK in 2018 was £14.6 tr of which property is £5tr and financial wealth £2.2tr – so a hypothetical one per cent tax on all property and financial wealth would yield £70bn a year, and just on property would be £50bn per year. Any such tax should be charged on assets above a certain level, which would then yield less than the estimates given here.

Yet the tax take from wealth is tiny, with the UK tax system disproportionately dependent on taxing income. In 2015/6, the combined revenue from existing capital taxes – stamp duty on property transactions and shares, capital gains and inheritance tax but excluding council tax – raised about £27bn a year, some 3.9% of all tax revenue. This accounts for less than one per cent of total private asset holdings.

The case for higher taxation on personal and corporate wealth is being widely recognized. Before the 2017 November budget, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research proposed an annual tax on net wealth (assets minus liabilities) above £700,000 (including residential property) to replace three existing capital taxes on inheritance tax, capital gains and dividends. A tax set at 2 per cent would raise £72 billion (gross).

The scheme would may have been unpopular in 2010, but might be much more popular now given that the public accept that we need to find a way of paying for social care and are unconvinced by Johnson’s plan. This is surely an area where KS should be out with all guns blazing!

Danny Dorling

I was one of the people earlier suggesting taxing wealth would be difficult. I don’t think I explained myself well. It is not the taxing of wealth that is difficult, that is easy. Ireland showed how it could be done on property with a progressive property tax where the percentage taken rose according to the value of property. They did it in an extremely short amount of time when forced to by the Troika in the Eurozone crisis at the start of the last decade. When that process began, they had no “gazetteer” – no universal register of properties – let alone any decent sets of valuations.

The best systems of wealth taxation make paying the tax annually part of the way you claim and maintain a record of your ownership of property. You can chose not to pay the wealth tax if you wish to gift that wealth to the state. You can also argue that your property is worth less than the valuation of the state. However, when you then come to sell that property, you may find that buyers don’t wish to pay more than you have said it is worth. Wealth taxes should also decrease the value of property which would not be a bad thing. So my concern is not with the idea of wealth taxes.

My concern is with suggesting it – and suggesting introducing a wealth tax to pay for the NHS/Social Care, without suggesting all the other mitigations you would do at the very same time that would make it appear plausible to many people.

But so many mitigations are needed that you end up needing a whole manifesto to explain them. I’ll give just one example. A large group of people in their 40s and 50s who have managed to get a mortgage now talk of their home as their pension. Their various precarious jobs have meant they have no decent pension, and although they may now be being auto enrolled into a pension. It is not one where they can envisage a future of being able to “keep the thermostat on 17 in their old age” as it was recently put to me by one home owner (still paying off their mortgage, and with the annual average income of the UK). What they plan to do is sell their home when they retire, downsize and use part of the savings to (among other things) pay the gas bill in winter.

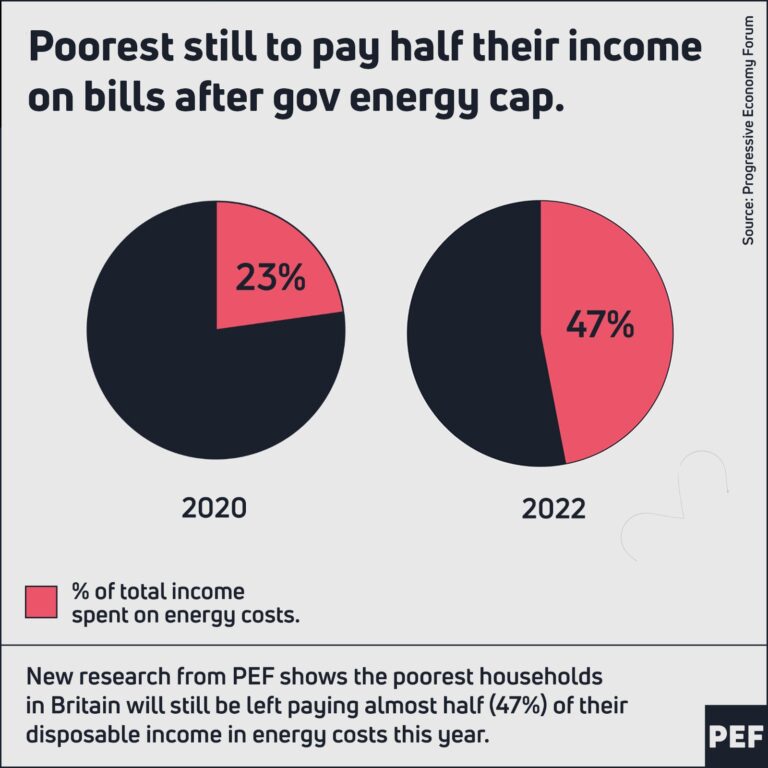

If we suggest a wealth tax, taxing away a slice of what they see as their savings every year without also suggesting how pensions will be improved, then in the mind of someone in that position your policy will condemn them to an old age of being cold. Gas and electric bills have just risen very quickly so these bills are on peoples’ minds at the moment. In effect, for them a wealth tax is an annual tax on their future pension. And quite a low pension at that.

I think this is one of the dangers of talking about raising a new tax to pay for one thing, when all the others things are not considered.

My preference is to keep taxing and spending separate, not hypothecated. So talk about rebalancing the tax system to make it fairer – with the emphasis always on fairness. And I would bring the overall level up to what is normal in Germany (almost identical to what Labour promised in their 2019 manifesto). Talk about bringing in taxes on wealth solely for the purpose of increasing fairness, not to pay for a particular policy, but also partly to allow other less fair taxes to be reduced, and partly to allow overall public spending to be at normal European levels.

On spending, we shouldn’t talk too much about the amounts of money in each sector, but much more about what it is you actually want to see. Something that is very good need not be very expensive. The Finns spend less as a share of GDP on their school than we do on ours, but their schools are much better. In contrast, we spend an enormous amount on our now almost entirely privatised universities, but we don’t see that as a tax. In the USA, they have the highest spending on health care in the world – and in general poor health.

I’ll stop there, but hope it helps explain my worry about suggestions of introducing a wealth tax to pay for health and social care.

Josh Ryan-Collins

I agree governments should not hypothecate (and I’m amazed HMT broke its own golden rule on that in this case) both because it can lead to less politically popular services getting neglected but also because it embeds the idea that we can’t pay for stuff unless we raise the money first which is simply not the case in sovereign currency issuing nations.

Having said this, the Tories have hypothecated and they have just implemented the biggest tax rise in living memory indicating (perhaps) a seismic shift towards the centre on economic policy. This threatens Labour in quite a serious way if they can’t differentiate themselves effectively. The way to differentiate is to focus less on the amount of tax needed and for what (as you say Danny and Sue) but on how that tax should be raised and from whom in a way that is both socially just and economically sensible.

It is not sensible to be withdrawing purchasing power from workers and businesses when the economy remains fragile. But the even bigger issue is that tax needs to be seen as a key tool via which issues like inequality and falling productivity can be addressed via pushing against economic rents and favouring investment and wages. This NIC tax hike broadly does the opposite. If you make your money from rental income, interest fees or capital gains, don’t pay a penny more, in contrast to workers and firms. The chart below from Resolution Foundation shows how crazy the situation is:

Will Hutton

I am all for taxing capital and am in violent agreement that too much capital taxation has been allowed to atrophy: no revaluation of residential property since 1991 so that council tax yields a fraction of the old rates, de facto semi-voluntary inheritance tax, too low capital gains tax, etc. During the 1945-50 Labour government tax on estates ran at 10 per cent of all tax revenues. There is huge scope to increase capital taxes, and as Josh has argued, property is immovable.

Stephany Griffith-Jones

I agree with Will on practically all points – including the extraordinary absence of a revaluation of residential property since 1991, which includes periods when Labour was in power! An effective and fairly high inheritance tax is very desirable, as one of the structural problems is perpetuation of wealth concentration via inheritance.

Stewart Lansley

Just on Danny’s points:

1. ONS wealth figures are net wealth and any wealth tax on residential property would be net of mortgage debt, so Danny’s examples would not be affected.

2. Yes, we must do more to make the existing taxation of income fairer, for example by reform of National Insurance system, but this would not be enough on its own to create a more equal society.

3. As I argued in Return of the State, we are close to the limits of income taxation, So if we want to raise funds for improving social provision we need to turn to asset-redistribution, though this would require taking public with us. Wealth is much more unequally distributed than income – Top fifth hold 64 % of personal net wealth and 80% of financial wealth – and unless we tackle that we will not be able to reduce inequality and poverty on a sustainable basis. It’s perfectly possible to design a wealth tax system that is concentrated on top wealth holders.

Geoff Tily

The TUC have argued that reforming Capital Gains Tax is a much fairer way to fund social care than hiking workers’ and businesses’ national insurance contributions. But like President Biden’s notion of “work not wealth”, I want to make a broader macro argument that the interests of wealth and of labour are fundamentally opposed.

My Keynes Betrayed was concerned with restoring Keynes’s conclusion that the long-term rate of interest must be set permanently low. Since I have been at the TUC, it occurs to me that this rate should interpreted more broadly as the return to capital/wealth and should be compared with the return to labour. Keynes’s conclusion that “we must avoid [dear money] … as we would hell-fire” (Collected Works XXI, p. 389) then means that we orient the system to the interests of wealth at our peril.

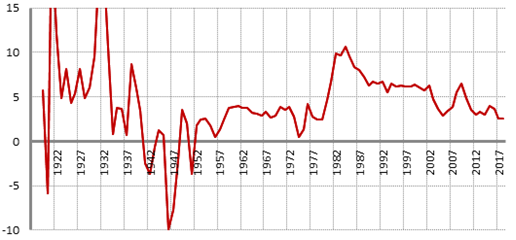

The below chart shows a measure of the real (inflation-adjusted) long-term interest on US corporate debt, going beyond the normal comparisons of rates on government bonds. Even this doesn’t capture well the experience since the global financial crisis, but plainly we know full well what has happened to the broader return to wealth versus the return to labour over the past decade. (I suspect US investment grade corporate debt has simply become increasingly regarded as retreating from risk – and this goes right back to dot.com bubble.) “Dear money” can be seen coming in rapidly from 1979 (in parallel to the ‘Volcker shock’), and interest rates were sustained some way above the post-war levels (and back to the 1920s).

US real interest rate

Josh’s chart from the Resolution Foundation is a nice one, not least because the timing of the key dislocation matches well the restoration of dear money on the above. Above all, this rise in returns to assets is a consequence, not a cause, of dear money.

Previously I had argued (following the General Theory chapter 22) that macroeconomic disarray comes in through overinvestment, but now I like a broader over-production/under-consumption (or rather, under-compensation) approach (it’s trade union friendly, has recently been revived by Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis [though Stuart Lansley had done so nearly a decade sooner], and is likely to be more correct!). Rather than spending to compensate for the underspending of labour, the wealthy speculate and so exacerbate over-production. This leads to unsustainable private debt, and ultimately meltdown; the fear here is Quantitative Easing has simply kicked the can down the road, with the risk of meltdown appearing later.

Tax on the wealthy can be part of the solution (as in the opening of the final chapter of General Theory), but to restore the balance to labour requires wholesale macroeconomic change that operates on a global basis. Hence my recent argument that ‘internationalism begins at home’.

We were convened in the first instance as a group inspired by Keynes, so I hope colleagues engage with this argument. On my view, it’s how Attlee, Dalton, Gaitskell, Bevin, Blum and FDR understood the world, helped them successfully to win office, and to begin to make real change.

Jan Toporowski

The real con trick in the government’s proposals is the claim that this is a solution to the social care crisis, when the funding for that is being explicitly postponed until the difficulties in the NHS have been overcome. So the social care funding is conditional on that same funding being enough to overcome NHS difficulties, a most unlikely prospect. The electoral con is the message that the residual of working people on proper contracts will get in their payslips that their money is going to be spent by the government not once but twice to solve both health crises.

Guy Standing

One cannot sensibly discuss how to pay for social care without a systematic view of what care entails, which encompasses its messy definition, who should receive it, who should receive money being spent on it, how they should receive it, and so on. Once one opens the Pandora’s box one should realise that any hypothecated approach, as implied in what the Tories are doing, makes no sense whatsoever. Hypothecated taxation opens the door to the worst features of utilitarianism,

The Government’s tax and NI rise is doubly regressive, since it lowers the earning of most paid carers at a time when their income and morale are abysmally low. If a government does not alter the structure of the so-called ‘social care industry’, the primary beneficiaries of pouring more money into it will be the private equity interests (mostly foreign capital) which are plundering money being spent on social care. Removing private equity should be a top priority. And any funding scheme that relies on means-testing will accentuate what is a highly regressive scheme, not reduce it.

More generally, there must be a huge shift in taxation from earned incomes to wealth of all kinds and to incursions into the commons, which means much increased eco-taxation. Ironically, incomes are nowadays the least taxable, with the UK being a rank outlier in the very high extent of tax evasion by high-income earners. But changing the incidence of taxation should be the secondary concern to the need to restructure the care sector. The social care crisis is a structural one, not primarily a fiscal one. Perhaps a Royal Commission should be set up to devise a proper plan for an integrated, universally-based system.

Sue Himmelweit

I agree strongly with Danny about not muddling up comments on taxing and with those on spending. But I don’t think that means that Labour should comment soley on alternative forms of taxation.

The first thing that has to be said about the so-called plan for social care is that it isn’t one, that it won’t be doing anything to improve provision nor even get back to the already failing system that we had in 2010. As the party that stands for protecting the vulnerable by collective provision this must be Labour’s first call. If they are commenting on a policy on social care, their first comment should be on social care and the need for it to be adequately funded (in the sense of enough spent on it), not on different forms of taxation. This should be true of PEF too!

Labour should also make clear that we could benefit from an overhaul of the tax system, so that it taxes, at the very least, gains in wealth. Reforming CGT so that is charged at the same rates as income tax with no specific tax allowance (except to exempt gains too small to count) would be a first step. And I would also like to see inheritance tax replaced by a receipts tax covering all ways of receiving wealth, also taxed at income tax rates (with some allowance for spreading a windfall over a few years). This way all ways of gaining wealth would be taxed at a reasonably high rate. This to me seems easier and more logical than taxing wealth itself at a low rate.